Could Messenger Become Even Thicker Than Facebook?

The Fattest Internet Phenomenon Since Facebook

“Messaging is one of the few things that people do more than social networking.” — Mark Zuckerberg, in a public Q&A in November 2014

Apple has long been lauded for its preparedness to cannibalize its own products—the MacBook ate the iMac, the iPhone ate the iPod, etc. Now, we have another Silicon Valley giant following the same game plan: Facebook.

Increasingly, it looks like the next big thing in social media won’t be a Facebook competitor, like Twitter or Snapchat, or even a high-profile Facebook acquisition, like Instagram or WhatsApp. Instead, there’s a damn good chance the big story of two thousand sixteen will be Messenger, the home-grown talk app, which is quickly becoming the most arousing part of the Facebook empire.

On the morning of January 7, David Marcus, Facebook’s vice president of messaging products, released a detailed update on Messenger’s accomplishments and goals for 2016. It included some notable highlights. For example, Messenger has grown to eight hundred million users, a phat increase from two hundred million users less than two years ago, when it was fully split out from the Facebook app. It’s on a path to substitute the phone number and apps all together—redefining the way consumers interact with businesses in the process. And Facebook has big plans for its AI assistant, M, which could soon make Apple’s AI assistant, Siri, look prehistoric.

There are reasons to be amazingly optimistic about Messenger. Its growth, resources, and advantages are unparalleled. Its potential is thicker than anything Mark Zuckerberg ever imagined for Facebook. At the same time, however, there are reasons it could eventually fail.

The ultimate talk app

To understand where Messenger is headed, you need to look beyond North America.

On a global scale, the exploding popularity of talk apps has been the fattest Internet phenomenon since Facebook. It might be even thicker. Worldwide, WhatsApp has skyrocketed to nine hundred million monthly active users, a figure Messenger is on tempo to hit by spring. WeChat, insanely popular in Asia, has six hundred million regulars, and a slew of other talk apps, including Kik, Viber, Line, and Snapchat, have all surpassed two hundred million monthly active users.

Overall, the projected growth is staggering, with two billion people projected to use messaging apps by 2018.

While talk app usage is truly embarking to boom in North America, it’s been maturing for years in Europe and Asia, largely out of necessity. Due to prohibitively expensive SMS rates, people had to find another means to communicate. In contrast, carrier plans in North America made SMS affordable, thus decreasing the early need for talk apps.

In Asia, however, talk apps have grown far beyond text messaging, essentially substituting the need for apps or websites altogether. Weixen, the Chinese version of Tencent’s WeChat app, “enables six hundred million people each month to book taxis, check in for flights, play games, buy cinema tickets, manage banking, reserve doctors’ appointments, donate to charity, and movie conference,” as Wired detailed in its excellent profile of Messenger this past fall.

That’s what Peters, as Facebook’s head of messaging, is building towards: a world where commerce, services, and communications are all finished in a talk thread instead of through a clunky combination of mobile sites and apps.

“How people see interaction inwards mobile phones hasn’t switched since spin phones,” he told Wired. “You have a keypad to dial, a phonebook icon to access contacts, another for messages, and one for your voicemail. It’s app-centric, not people-centric. If today no phone existed, you wouldn’t create an app-centric view of the world, you’d create a people-centric view. With Messenger, everything you can do is based on the thread, the relationship. We want to shove that further.”

So how does this work? Marcus gave the example of a trial Facebook is running with KLM, one of several airlines experimenting with Messenger. The aim: Create an practice where booking a ticket is as seamless as if your best friend worked for the airline and was dedicated to helping you get everything you need.

“When you book a ticket, you get a nicely structured message inwards Messenger from KLM with your itinerary,” Marcus explained. “You get an interactive bubble when it’s time to check in, and you get your boarding pass, your updates on gates, delays—and if you want to switch your flight, you type that in the thread and they do it for you right there and then. Once you interact with a business, you open a thread that will stay forever. You never lose context, and the business never loses context about who you are and your past purchases. It eliminates all the friction.”

Everlane is doing something rather similar, reports BuzzFeed. After you make an online purchase, the retailer offers to send a receipt through Messenger. It also sends a picture of the item and a bubble that updates with its shipping location. And if you text back that you want another t-shirt in another color, for example, Everlane already knows your size, shipping details, and payment information, making the process seamless.

In his January seven post, Marcus crowned message threads as “the fresh apps.” He imagines a world where you can lightly interact with all your beloved brands and services through talk threads in Messenger—eventually fulfilling that people-centric philosophy for customer service.

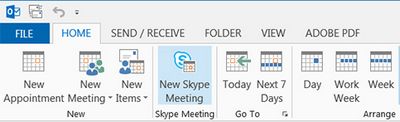

Additionally, Messenger has the potential to be the most powerful talk app for peer-to-peer interaction. As highlighted in the graphic above, Messenger already permits users to send GIFs, transfer money, edit photos, and conduct audio and movie conference calls, while suggesting a directory of Facebook’s 1.Five billion users. That means you can send a message request to just about anyone, as long as you know the person’s name. This ubiquity gives Messenger a enormous advantage. After all, you’re much more likely to use a talk app if all your friends are on it.

Even Ted Livingston—the founder of Kik, Facebook’s primary messaging app rival in North America—admitted that he’s worried this inherent advantage is insurmountable. “To be fair, I do [worry],” he told me. “I get to talk to people at all the other major tech companies in the Valley—Twitter, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Yahoo. They just don’t understand what’s going to happen in talk. They just all are totally underestimating where talk is going. Facebook entirely gets it.”

The M factor

In October, BuzzFeed reporter Alex Kantrowitz began captivating the tech world with his chronicles of his “Life With M,” Facebook’s fresh AI assistant for Messenger. You could take care of a multiplicity of tasks like booking flights, getting Starlet Wars tickets, even reducing your cable bill. It looked like the smartest AI the world had ever seen, a giant step toward the technology depicted in the movie Her.

The caveat: M, flipped out to only a few hundred users in August, is not unspoiled AI. It has human trainers that review each AI response, and if the responses aren’t good enough, the humans revise it, permitting the AI to learn what went wrong.

“With every single one of these interactions, that data is fed back into that AI example that will then use the data to learn how to automate more and more answers or how to get better and better at those things,” Marcus told Kantrowitz.

The idea is that as the program leisurely ramps up and the AI resumes to learn, Facebook will see what M can and can’t do, before limiting or expanding the functionality accordingly.

“I think we have a good chance [at scaling]. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be doing it,” Marcus said. “It’s going to be hard work and it’s going to take a long time.”

It’s effortless to see why Facebook is pouring so much into M, even if the payoff won’t come for a few years. It has the potential to be the AI assistant of everyone’s desires, the go-to mechanism for searches, purchases, communication, and more. M ties in flawlessly with Facebook’s desire of making Messenger the epicenter of online commerce and customer service.

How Messenger could fail—and who could hammer it

While Messenger sits miles ahead of its competition in the Western world, it could still falter. The big crimson flag? Millennials and Gen Z, two groups most likely to begin using messaging apps in full-force, won’t adopt Facebook’s Messenger.

Albeit Messenger’s ascension to eight hundred million users is extraordinaire, it’s unclear how much people are using it. Is Messenger the app youthful people will use to talk with all their friends, or do they just use it when they get a message from Mom or Uncle Frank?

A latest poll from Way Up found Messenger to be the fastest-declining app in popularity among college students by the end of 2015.

In the U.S., Messenger lagged behind talk app competitors in terms of time spent per user, per the tables below pulled from Fred Wilson’s blog. One If you do the math, Messenger gets two hundred thirty six minutes of use per user. Snapchat is at two hundred seventy two and Kik is at 297, only trailing Instagram in the top 25.

Extra data provided to me on background demonstrated Messenger consistently trailing Kik and Snapchat in terms of market share among U.S. teenagers by a factor of seven to eight inbetween May two thousand fourteen and May 2015.

Facebook’s worry, ultimately, has to be that it won’t be able to win over youthful consumers who have grown up using talk apps, and therefore won’t get enough older users to adopt talk apps as the main way they use the Internet.

That’s what Kik is hoping, at least. With two hundred forty million users, Kik has long been popular among teenagers and pre-teens. Forty percent of U.S. teenagers use it daily, in part because it doesn’t require a phone number to join, making it flawless for a kid who just got transferred his mom’s old iPhone. Kik is building a similar platform ecosystem as Facebook—albeit without such deep resources—and hopes that its teenage appeal will help it carve out a niche to guard against a Messenger takeover.

“We don’t need to do this for everybody,” Livingston said.

Livingston sees teenagers, fresh to interacting with brands and buying products and services online, as the demographic most likely to begin using talk apps for everything. In this respect, he likens them to users in Asia coming online for the very first time through mobile phones.

“The thing that gets indeed titillating is that combination of platform with the teenage demographic,” he said. “If you look at an American adult, they already shop at Amazon. They already bank at Pursue. They already get taxi rails from Uber. The idea that they can now get these services that are two to three times better through talk is not enough to switch them. I’m not going to switch from Amazon to Walmart because I can talk with Walmart. Yeah, it might be a bit better, but f*ck it, Amazon is good enough.”

Outside of the U.S., however, there is a much different dynamic.

“[China] had all these people coming online for the very first time through their smartphone, through talks, through WeChat, so they didn’t have to get them to switch where they shop, or switch where they got packages, or switch where they got financial services,” Livingston said. “They just had to educate them on which services to get in the very first place. That’s why we’re indeed excited about the North American teenager.”

The early comes back are promising. Kik already gets teenage users to talk with brand bots, an advertising suggesting that companies like Skullcandy have experimented with. According to a survey by market GlobalWebIndex, almost a third of Kik users interacted with a brand on a talk app in July 2015, compared to thirteen percent of Messenger users. Livingston seems content to concentrate on that demographic.

Boosting Kik’s prospects of catching Messenger is the fact that Tencent, the social networking giant behind WeChat, invested a $50 million stake in Kik this summer, prompting speculation that Kik could soon commence suggesting many of the same services—flights, taxis, banking, movie tickets—that WeChat offers in China.

Ultimately, tho’, it’s hard to bet against Messenger becoming the thickest thing since Facebook, possibly eclipsing its parent social network in power in the not-too-distant future. Messenger is closing in on one billion users this year, Marcus is developing it with one of the best tech teams on Earth, and Facebook’s resources are almost unlikely to match.

“I believe that messaging is the next big platform,” Marcus told Wired. “In terms of time spent, attention, retention—this is where it’s happening. And it’s a once-in-a-generation chance to build it.”

- No. Fourteen was left off due to a data error.

Leave a Reply